Class Newsletter Vol. 2, #1

The theme of this issue is Inovation in Learning or Education for Diverse Populations

Scholarship Plus, Part II of II by Soma Behr, (continued from Part I in our December Newsletter issue)

Less than a year after its birth, in June 2010, Scholarship Plus hosted a small but spirited welcome party in the cafeteria at New York Public Radio for our first class of six students, their families and friends. Each proud but anxious student also honored a teacher who had made the biggest difference in his or her life. Emotions ran high.

It is now ten years later, and we have just accepted our largest class of 13 scholars – more than double our original class size. This brings the total to 77 students supported through college by us. Our welcome party is now triple the size and growing. The program has really taken off.

It is now ten years later, and we have just accepted our largest class of 13 scholars – more than double our original class size. This brings the total to 77 students supported through college by us. Our welcome party is now triple the size and growing. The program has really taken off.

The truth is that I had a lot of help in the years in between. Getting that help turned out to be quite easy. That’s because there is an enormous desire in people like us to help students like ours who have great potential but have been forgotten or mistreated by our public education system.

Our track record is terrific. So far 100% of our students have graduated from college. That is almost unheard of. Most colleges and scholarship programs miss that target. And over 50% enroll in graduate school within the first couple of years after finishing college.

Unfortunately, I think that things have gotten harder for our students and for those of us trying to help them. The divisiveness that has infected America and its politics does not stop at the college gate. Quite the opposite. On some campuses being Black, Hispanic or Muslim seems more difficult now than it was just a few years ago.

“Throughout college, I knew I had a community to support me in ways that my family

couldn't,through no fault of their own. When I felt alone watching my peers ask their

parents to read overtheir papers, or for internship connections, or even for relationship

advice, while I struggled and my immigrant mother couldn't quite grasp what I was doing

in college, messages from Scholarship Plus would remind me that I wasn't alone, and

that I had a caring, kind, and supportive community just a phone call away. So,

whenever anyone asks me about Scholarship Plus, I make sure they hear the "plus".

Because the plus matters.” —Sino (Vassar College, Class of 2016)

Even though many colleges are making a greater effort than before to admit low income students of color, data shows the graduation rate for low income students has stuck at around 11% in recent decades. Meanwhile graduation rates for better-off students have risen from 46% to 61%. And when I say “low income”, I am talking about students (in our scholars’ cases) whose average family income is $22,000. This is below both City and federal poverty lines.

One problem is that low income minority students need more help on campus than most colleges will or can provide. And these students generally need more help than the students themselves know how to request from professors or college advisers. Research also shows that the failure to finish college can be a bitter wound for these young people . Their future income will be less than if they had graduated and many will still have to repay student loans. It is clear to us that there is an enormous need for programs like ours.

Last year I handed the baton to a younger colleague. After nine years, my Rolodex was fraying and my contacts list not growing fast enough. Our new Executive director is Kate Fenneman Stokes, who honed her Dskills running a large college scholarship program for the comedian Jerry Seinfeld. She has the experience and passion to take Scholarship Plus to 20 students a year, a goal we have had from the start. In the last year, we created a new Scholarship Plus board, which includes Anthony Jack, Assistant Professor of Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and author of The Privileged Poor: How Elite Colleges are Failing Disadvantaged Students. We have also brought aboard scores of young professionals as part of an Associate Board. Many of them were former scholarship students themselves, and are eager to help us build a strong support network for younger students.

On the money front, we’ve worked hard to find individuals donors and a few large foundations to support full scholarships at a cost of roughly $40,000 per student. We created another form of funding for smaller donors, who each commit to $1,000 annually for four years. To go from the 15 students we hope to finance next year to our goal of 20 per class will require substantial new funding. But it’s a goal definitely within reach.

On the money front, we’ve worked hard to find individuals donors and a few large foundations to support full scholarships at a cost of roughly $40,000 per student. We created another form of funding for smaller donors, who each commit to $1,000 annually for four years. To go from the 15 students we hope to finance next year to our goal of 20 per class will require substantial new funding. But it’s a goal definitely within reach.

As undergraduates, our scholars experience many diverse challenges, and we are there to support them – we can do this effectively because we know each student well, and they are willing to come to us.

One Saturday evening, we had to move quickly to help a student escape from a dangerous family situation and settled her in a room of her own in a new location with food supplies and advice for managing her safety.

When another student left her laissez-faire college because of a mental health crisis, we helped her frightened Spanish-speaking mother admit her to a psychiatric facility in the City. Later we found a unique program in the City to help her return to a different college, and arranged funding to support this help.

We introduced a bright sophomore student with no particular career goals to a powerful New York City lawyer who gave her a summer internship and set her on her way to becoming an associate at a prestigious law firm after graduating from NYU Law School.

We have built a new community, one person at a time. Scholarship Plus crosses traditional boundaries of class and race. Everyone involved shares a dream: that with some financial help and a lot of personal support , our collective efforts can change the lives of bright, determined students. ▼

![]()

Father to Son: A Heritage of Learning on Muskeget by Crocker Snow, Jr. excerpts from his book: Muskeget: Raw, Restless, Relentless Island

Crocker's five sons all had transformative learning experiences on Muskeget, passed down from grandad. The fourth generation is now participating in this intra-family tradition.

My dad was a Yankee, brought up in Boston and Buzzards Bay on Cape Cod. He was a lifetime pilot extraordinaire whose first license was signed by Orville Wright. He piloted 160 models of planes, and was still flying at 92 after more than 15,000 miles in the air. We made a rough landing strip in the smoothest driest land in the middle of Muskeget, and he flew us to our camp there many times.

For me, more even than my first hunting lessons with my father, holding a shotgun and using a duck call over decoys, is the memory as a teenager of being sent up on the camp roof in the middle of the night during a wind storm to secure the stovepipe chimney with wires so the smoke of our wood stove didn’t reverse itself. I have many great memories of my adventures there.

I continued the tradition of camping on the island with my sons, and they also have many memories from Muskeget. I encouraged my adult sons to dredge up some more stories of island life, and what it meant to them. It’s red meat.

Eldest son Adam, a star professional athlete, in his fiftieth year writes:

Muskeget recalls the incessant throaty call of gulls; a canvas of beach grass shaking to wind and framed by ocean the color of the sky. Sand with high-tide markings of stones, bones, and piles of black-dried eelgrass –spotted with white barnacles and salt crystals – unmoored lobster pots, stranded flip-flags and detritus from distant continents.

I experience exhilaration nearly every ‘first time’ I walk on this place after being dropped off by a boat or a plane or a seaplane. The engine departs leaving me – and once or twice, it was only me – on the island with the wind and the waves and the grass. I recall one time as a child literally whooping for joy as I trudged – laden with a duffel and hip boots – towards the distant goal of our camp. My brothers were beside me carrying their own cargo as we wound our way through the large prickly bush near the mouth of the ponds – halfway between the runway where the Navion had dropped us and the camp which was gradually coming nearer. I whooped with the spirit of the place and for joy at being part of it. My brothers understood and without any plan or forethought, we whooped together a time or two in celebration of the place.

I experience exhilaration nearly every ‘first time’ I walk on this place after being dropped off by a boat or a plane or a seaplane. The engine departs leaving me – and once or twice, it was only me – on the island with the wind and the waves and the grass. I recall one time as a child literally whooping for joy as I trudged – laden with a duffel and hip boots – towards the distant goal of our camp. My brothers were beside me carrying their own cargo as we wound our way through the large prickly bush near the mouth of the ponds – halfway between the runway where the Navion had dropped us and the camp which was gradually coming nearer. I whooped with the spirit of the place and for joy at being part of it. My brothers understood and without any plan or forethought, we whooped together a time or two in celebration of the place.

Adam’s brother Andrew, the most committed hunter and fisherman among my sons, remembers his first Canada Goose: you sent me off on my first goose ‘stalk’ over by Holdgates when I was eight or nine years old. You wanted me to flush it with the expectation that it would fly towards you – a formative event in cementing my love and passion for waterfowling. I’ll certainly never forget the feeling of walking back towards you across the beaten-down marsh grass around the old blind with goose in hand, and I’m sure, a huge smile on my face.

Another, to me, déjà vu incident: in the middle of the night during a strong nor’easter, you got up to put an old fish net that you found in the attic across the picture window facing out to the marsh, for fear the 40 to 50 mph wind (with stronger gusts) might shatter the glass – Josh and I were sleeping right underneath it! When we awoke the next morning, with the wind still howling, the high tide was lapping at the back steps. I remember feeling, at that moment, very small and inconsequential in the grand scheme of things.

Josh, long Alaska-based, answers the memory test in staccato-style:

- Playing in the sand surrounding the camp, creating intricate micro-ski areas. The sand

was the open slopes,the shrubbery was the forest. - Stalking among the dunes with the old WWII rifle, imagining I was storming the beaches

of Normandy. - Sitting on the point pass-shooting with Andrew. I don’t think we dropped a single bird,

but it was so fun tothrow the lead out there. - Lying down on the sand and falling asleep behind the SW blind, while Andrew hunted

hour after hour. - Stepping on the clam rake and putting a hole between my toes.

- Watching from the skiff while Mom and Mrs. Robertson struggled against the riptide current

until they were exhausted. Then standing outside camp watching Mrs. Robertson retch

up saltwater. - The buzz/tweet from the cockpit during take-off in Gingrass’ seaplane. It always sounded

as if the plane waswarning us of imminent failure. - Burning trash on the beach as we cleaned up camp before exit. That was always a kid job.

Connor, the youngest, now an undergrad at Texas A&M, remembers a cold water dunking:

I’ll never forget bagging my first duck at the Lagoon during a frigid Thanksgiving. Overeager to claim my prize, I was halfway into the water before the shotgun echo ended. A half second later, I was plunging off an underwater mud shelf that the water was too murky to betray. I got the duck, a Sheldrake, going in up to my chest, and then sat on the bank with our dog Keen Eye (Kenai) soaked and smiling broadly.

The postscript was the gun was undamaged, grabbed from him as he ran for the water. And it was a long tramp back to camp for him to shed his rubber hip boots and damp, clammy hunting clothes.

My son Nick, age thirty, recalls when he was twelve and was allowed to join a NOLS (National Outdoor Leadership School) overnight ocean kayak adventure.

It was a beautiful day and no problems on the way over (from Nantucket), but I remember feeling the brisk breeze and seeing whitecaps the next morning when we got up and the main NOLS instructor teaching us how to roll over in the protected lagoon. I had never experienced arriving at or leaving the island by kayak, which had a very different feel, more remote, isolated and foreign than the friendly confines of a scallop boat.

It was a beautiful day and no problems on the way over (from Nantucket), but I remember feeling the brisk breeze and seeing whitecaps the next morning when we got up and the main NOLS instructor teaching us how to roll over in the protected lagoon. I had never experienced arriving at or leaving the island by kayak, which had a very different feel, more remote, isolated and foreign than the friendly confines of a scallop boat.

The return trip was different. Almost immediately, our dozen kayaks were fairly spread apart. At the bottom of the waves you could really only see a wall of ocean, but being with an experienced kayaker from New Zealand made things easier. I just needed to paddle without thinking. It was probably not that long, but it felt like an eternity that we were bobbing from peak to trough of each wave. Touching down on the beach I was about as happy as I have ever been to arrive on land in my life!! All parties were accounted for, with a couple scooped up by lobster boats, so in the end we all made it safe and sound. The experience reminded me that we are at the mercy of the weather and ocean in many instances that we put ourselves into. The ocean around Muskeget had never felt as wild as it did that day.

If anyone would like a copy of my book, please give me a call at (978) 395-1961. ▼

![]()

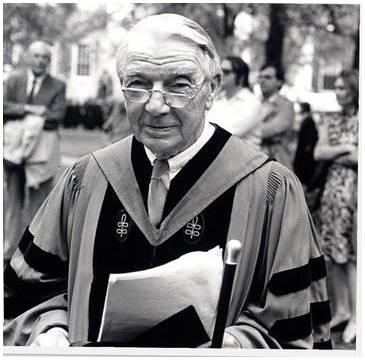

On Teaching and Learning by Gilbert W. Merkx, ‘61

Winston Churchill, speaking on November 4, 1952 in the House of Commons, famously observed, “Personally, I am always ready to learn, although I do not always like being taught.” Like so many of Churchill’s epigrams, this comment is memorable because it rings true to common experience. We love to learn, but to be taught can be a drag.

Winston Churchill, speaking on November 4, 1952 in the House of Commons, famously observed, “Personally, I am always ready to learn, although I do not always like being taught.” Like so many of Churchill’s epigrams, this comment is memorable because it rings true to common experience. We love to learn, but to be taught can be a drag.

The transition from being taught to being a teacher came rather suddenly for me. After graduation I spent a year in Peru on a Fulbright studying anthropology, and then I enrolled in the sociology PhD program at Yale. As soon as I finished my course work at Yale, the department asked me to be a Teaching Associate, an offer I was afraid to refuse. I have been teaching ever since, for a total thus far of 55 years in the classroom. The challenge of teaching in a way that stimulates learning has been a constant preoccupation. I’ve tried a lot of ways to teach, learned about a lot of techniques that failed, and learned a few things that worked.

I first learned about teaching while we were students at Harvard. We had a wonderful curriculum, which included a distributional requirement that made each of us take a year-long course on a humanities theme, a social science theme, and a natural science theme. We were lucky. Not too long after we graduated that curriculum was junked in favor of a curriculum allowing more specialization.

The humanities course that I chose was Humanities 2, “The Epic and the Novel.” John H. Finley, Jr., Master of Eliot House, taught epics in the fall term, and John M. Bullitt, Master of Quincy House, taught novels in the spring term. Finley was an entertaining showman, strutting around the stage of Sanders Theater with a pointer, making eye contact with the students, and speaking without notes. He illustrated his points by spouting outrageous and entertaining metaphors, many of which I still remember and sometimes use in my own classes. I was fascinated by him and learned to love the great epic poems. In contrast, Bullitt was serious and well-prepared. He stood behind the lectern and read his lectures in a something of a monotone, without making eye contact with us. As the second semester went on, I found that I was having trouble staying awake. The novels were great, but the lectures, in spite of their excellent content, were deadly.

We also had tutorials in our houses. My tutor was Arthur S. Couch, a psychoanalytically-oriented psychologist. These were not one-on-one tutorial as at Oxford, but small group tutorials with about half-a-dozen students. Each week we were assigned readings and had to answer Couch´s questions about the content. If one was not prepared, there was no way to hide that fact. The challenge of the weekly face-to-face encounters forced me to prepare carefully. As a result, I learned a lot about Freudian psychology and small-group dynamics.

What I learned from the Hum 2 lectures was that the large lecture format requires the teacher to be entertaining. What I learned from Couch’s tutorial was that the teacher must question the student. The content of the lecture is important, but it will not be absorbed without drawing the attention of the student through showmanship. The tutorial, in contrast, is a version of Socratic method in which through questioning the teacher guides the student to self-discovery of the content. These lessons were to be useful later when I lectured to large classes or when I taught tutorials or seminars. However, much of the time I was to be teaching medium-size classes of twenty to thirty students, which posed a different challenge. More on that later.

Even when we were students at Harvard, the U.S. higher education system was growing rapidly and public institutions were getting larger and larger. Tutorials were too expensive for mass education, and good lecturers were in short supply. In typical American fashion, a search began for ways to solve these issues with technology, a search that continues. Among the solutions presented, in more or less chronical order, were: correspondence courses, teaching machines, taped lectures presented in classrooms with TV screens, distance learning through television broadcasts, and most recently, MOOCs (massive open on-line courses).

None of these solutions lived up its promise. Correspondence courses attracted a very small clientele. Students hated teaching machines. They also hated taped lectures. Distance learning programs by and large did not attract enough enrollments to be economically viable. Despite enormous enthusiasm, considerable investment, and the participation of faculty from prestige universities, MOOCs basically failed. Drop-out rates from MOOC enrollments were exceedingly high and few students finished.

My own career as a large-class lecturer began as the result of such a failure. The former Chairman of the Sociology Department at the University of New Mexico (who had hired me away from Yale), persuaded the administration to equip the largest lecture hall available with an array of forty large television sets suspended from the ceiling. He then taped all his lectures for the large introductory course in sociology. This was announced with great fanfare in the student newspaper. After a cameo appearance for the first class, the professor disappeared, and the tapes were played for the subsequent classes. There were still Teaching Assistants, who led weekly discussion sections.

The TAs reported students were dropping out of the class like flies. The new Chairman then called me into his office and asked me to take over the class while there were still students left. Again, I could not refuse. I had the television sets turned off, walked onto the lecture stage, and pretended that I was John Finley. I lectured without notes, told stories, used outrageous metaphors, asked questions of the students, and encouraged them to ask questions of me. There were no more drops. However, I had to teach that same course for several years until the department hired some decent lecturers.

Eventually I developed strategies for teaching middle-sized courses, combining elements of the Socratic method with showmanship. The course I am currently teaching, called “Theory and Society,” makes use of these techniques. At the start of the class, each student must turn in a one-page discussion of a concept introduced by the reading assignment. I begin the class with questions about the reading, calling upon students by name to answer. If the student cannot answer, I call upon another student by name. This exercise takes about fifteen minutes. Then I lecture about the topic using as many metaphors and real-life examples as I can. Then I take questions from the students. Finally, I end by giving the class some clues about what to look for in the next readings for the class.

There are some downsides to this approach. The class is full, with 35 students, and it meets twice a week. This means grading 70 short papers each week. I have a TA. So I grade all the papers from one class and my TA grades all the papers from the next class. I also give a mid-term exam and a final exam, which I grade myself. It’s a lot of work. But the class always has a waiting list and the evaluations are positive. If I were younger and under more pressure to publish, I would have to spend less time on the class. But I retire at the end of this semester, so I feel free to enjoy teaching this way.

After all these years in the classroom, it seems to me that the gold standard for teaching is still the tutorial using the Socratic method. It is also the most expensive way to teach, making the “gold” standard an apt metaphor. However, if it helps students learn to learn for themselves, it is a good investment. ▼

Two John Finley Metaphors as recalled by Gilbert Merkx

Two John Finley Metaphors as recalled by Gilbert Merkx

The Poet and the Squire

We all enter life as peasants; at one with the world we have been given. We take this world for granted, and we take for granted that we are part of it. But then, as we grow older, we begin to realize that we are unique and different from the rest of this world. This is the process of individuation. Once we realize that we are unique individuals, we are estranged from the world we once took for granted. We face the challenge of developing a new understanding of the world and our place in it.

There are two paths to understanding the world and our places in it. The left-hand path is the way of the poet. The poet sees the world through words and ideas. The right-hand path is the way of the squire. The squire sees the world in terms of people and institutions. Both are valid paths, and if followed to the end will lead one to understand the world and one’s place in it. Then the circle of life is complete. At that point we become saints, once again at peace with the world that we entered as peasants.

The Compost Heap

My lectures are compost heaps. Every year I throw a new layer of ideas on top of the heap of old ideas. Then I rake the heap, mixing the new ideas into the old ideas. Whatever floats to the top I use in my lecture. Sometimes these are old ideas, sometimes new ones. This insures that I never give the same lecture twice. ▼

![]()

Distance Education? By Andrew Kahr

A long time ago, certainly before the Internet, I informed a client who was head of Marketing at AT&T (which still operated the great majority of US telephone lines) that “The office of the future is in the home.” I anticipated that this would both result from and elicit vast qualitative as well as scale enhancements in telecommunications. Much later, I saw that I had been dead wrong.

There was AT&T’s PicturePhone, then Video Conferencing (“our Chairman is very excited about this!”) – and finally Skype and the rest of the Internet. It still didn’t matter, they did not replace offices to any material extent. I had, however, amazed my client with the quite correct observation that “the most expensive business communication is face-to-face communication”.

But there has proved to be no substitute for physical presence in most cases. Friends of mine travel for days – just to attend meetings, not to visually “inspect” anything. I have had the privilege of questioning them at length about why “is this trip really necessary?” There’s no convincing answer, but no boss or counterparty is inducing or compelling them to continue these disruptive and inefficient travels.

That brings us to “distance learning.” Going back to Land Grant days, 19th Century, many state universities have used this auxiliary means to offer courses for credit. This was deemed necessary in order to make college education available to all of the state’s residents. You can get at least a BA without leaving home from some of these universities. But very, very few people ever did. Maybe in the past that could have been blamed on the slow speed of the mails, or on the student’s need for visuals. Not anymore.

With the advent of the Internet, I had high hopes that worthy people all over the world would be able to obtain degrees and other valuable credentials remotely at very low cost. However, after almost ten years of varied experience and engagement with these efforts, I’ve concluded that once again I was wrong. Very likely for some of the same reasons, plus others.

Let’s put aside whether getting drunk at football and basketball games, having roommates, and participating in student organizations are invaluable elements of the college experience. For me, they certainly were not. Never mind labs – I can make a strong case that at least in many instances, “virtual labs” are much more effective. The most fundamental problem seems to me to be social – hence quite possibly genetic, evolutionary in origin.

In Cambridge, you’re surrounded by people who go to class, take notes – for me, hopelessly inefficient and undesirable, but research says it’s salutary overall. You find it hard to avoid talking with others undergoing the same demands and stresses. They’re headed towards passing and graduating. It’s this that gives you a decent chance of running with the pack and getting to the goal. “I’m hopelessly behind in everything” doesn’t make friends. It invites shunning.

Contrastingly, you’re much less likely to do the work, turn it in and pass the tests, while living “at home,” and having limited if any contact with others facing the same challenges. Adding a job makes this harder. To say the least, Harvard need not fear losing the students it wants on campus because they prefer distance education.

After up to a decade of experience offering no-credit online courses, a few very reputable institutions have fairly recently started to offer online for-credit courses and degrees, with proctored tests. These are at BA and MA levels. But they are getting very low enrollments.

In general, tuition for distance education has been around ½ of campus tuition. (Campus entails heavy additional living expenses for most students.) They price about the same for online as they had done using the US Mail!

Contrariwise, online non-credit education, primarily via “MOOCS,” Mass Open Online Courses, continues to expand. There are now many thousands of courses available, the great majority from “real” institutions. Total enrollment has included millions of people, worldwide. The courses feature short lecture videos (generally with transcript available); quizzes and exams. Students can write on “forums” though few do so, and there are occasionally written assignments, graded by multiple other, random students.

About 5% of those who start such a course finish it, mostly “lifelong learners” as well as other college graduates with career ambitions. Most pay nothing for the experience, and the MOOC’s are consequently unprofitable. Hopes to monetize them fail, and the most prominent packager, Coursera, has run through several CEO’s, including a former President of Yale. A great many universities worldwide offer their MOOC’s independently, without explicit reliance on a packager.

Roughly, MOOC’s are an alternative to e-books but differ from e-books in being (at least a little) interactive; bite-sized (usually around 1/3 as many lectures as a semester course); and free. I think it’s valuable to have this alternative. It enables us to experience what courses in China, Russia – and even at Harvard actually contain. This was never before possible for almost anyone.

Roughly, MOOC’s are an alternative to e-books but differ from e-books in being (at least a little) interactive; bite-sized (usually around 1/3 as many lectures as a semester course); and free. I think it’s valuable to have this alternative. It enables us to experience what courses in China, Russia – and even at Harvard actually contain. This was never before possible for almost anyone.

Prof. Sandel filled the Sanders Theater for his Justice course. The actual lectures were filmed.

Quality and subject matter of MOOC’s are highly varied. For instance, UC Berkeley offers a Bitcoin course under its name which was prepared entirely by undergraduates. In one of their lectures, you can hear “Our mission is to promote Bitcoin.” I suspect serious, direct financial conflicts of interest. I complained, to no avail. “The department chair must have approved it.” This course is offered through EdX, the #2 platform, controlled by Harvard and (to a greater extent) MIT. It strengthens my conviction that EdX may be a bit selective as to the institutions whose courses it will offer—but never about content.

Now for a thought experiment. Suppose technology advanced to a perfect “virtual reality” capability. Would that make online competitive with campuses? I say it would not. We could put students in a virtual classroom. But that wouldn’t enable the social interactions that occur primarily outside the classroom, much less the competitive pressures that carry so many of us through the incredibly effortful undergraduate grind. ▼

![]()

Learning Design: from Theory to Business Application by Tom Blodgett

In the early 60s, Francis Mechner, PhD, a behavioral psychologist teaching at Columbia formed a company with a Columbia Law student. They set out to apply B. F. Skinner’s learning theory, notably Operant Conditioning, to business and institutional training needs, initially working only with theories of animal behavior. Learning Design starts with behaviorial specification, and "getting the right answer" becomes the psychic reward, first on a conceptual basis, then in an interpersonal setting. Early trial and error begins with the basic, and gradually (in suitably-sized steps) increases in complexity. The end of course objective is demonstrating competence in a large neumber of skills in relatively ambiguous situations. The company, Basic Systems, Inc. (BSI) obtained seed capital for a pilot project from Pfizer. BSI, after collecting a cadre of PhD psychologists, was acquired by Xerox in 1965, bringing several Harvard Business School graduates on board , I among them. The technical programmed instruction staff grew to nearly 30 before we realized that customizable generic programs or ‘products’ was the way to go, rather than grants and a scattering of one-off industrial projects. As Regional Sales Manager, then Manager of Product Development, then General Manager over eight years, I was part of creating a business with $7 million in revenue, that later grew to over $100 million.

I had the crazy notion to leave in 1973 to start my own firm, TBA Resources, Inc. I managed it successfully in New York as my primary professional activity until 2009 (36 years).

Rather than focus solely on behavioral training, I positioned my firm as an organizational consultant in the 80s and 90s. The evolution of a training and development function within Fortune 500 companies mirrored the evolution of the supplier firms. As a founder, I helped set up the Instructional Systems Association in 1978. The names have changed, and methodologies have become more media-centric, using video and computers, but the learning principles underlying organizational development remain the same.

- Develop awareness of the need for change, with practical case analysis and

discussion of what constitutes a high performer and what skill sets are critical. - Acquire new concepts that describe the context and need-to-know critical

procedures or skills. - Provide practice in application of desired concepts in simple situations, gradually

becoming more complex and more challenging. - Provide simulations of job experience to gain competence and proficiency in the

setting that participants face on the job. - Provide reinforcement on the job through coaching to sustain desired behavior.

- Strengthen the cultural acceptance of desired norms by recognizing desired success.

The evolution in learning methodology helped sponsoring organizations gain more enthusiastic participation of the learner, driving more change in how he or she executed the job. It ensured that the new methodologies are fully embraced within the management structure as well as in the front ranks.

Here is a partial list of the learning principles that we found achieved the greatest return on investment of time and cost for job-related learning:

- Gaining active participation, never having the instructor talk for more than 10 to 15 minutes,

engaging participants by charting all comments in discussion, and asking for examples.

- Providing immediate feedback at short intervals with workbook activity, and practice exercises

in pairs around the room. - Reinforcement of the models for participant, client, and observers in trio role-play cases.

- Applying the principle of successive approximations beginning with easy, and moving to complex

over a three-day period. - Backward chaining the ‘job theory’ so you always know where you are going.

- Focus on cue discrimination, so you know the When as well as the What, the How and the Why.

- Seeing the big picture so you can employ a strategy for sequencing, not just single responses,

with a rationale for why the strategy is appropriate. - Creating real-world simulations accurately depicting the job environment to ensure transfer of skills to the job.

- Giving coaches and team leaders expertise to run meetings to support the skill-sets.

My career choice was personally rewarding, since enhanced competence is highly correlated with enhanced job satisfaction. It gave me an opportunity to work with Japanese partners, and have three major Sales and Sales Management programs become the most widely used (of US origin) translated for resale in Japan. For some years we had a branch office in the UK, and conducted seminars there and in Europe. Another source of pleasure was that all our work took place over several days, in groups of never more than 24, so I could get to know everyone by the time I handed out the Certificates of Accomplishment. ▼

![]()

Not Your Grandfather’s Med School by Diane Jacobs

I borrowed the title from the headline of an article on changing trends in Med Ed written by Timothy Smith, a senior news writer for the American Medical Association in February, 2017. That sums up my experience when I joined the faculty of the newly approved College of Medicine at the University of Central Florida in 2006. I had not taught medical students since 1988 when I left the University at Buffalo. Since then, many stakeholders recognized that changes in the healthcare environment required changes in the content, delivery, and system of medical education. In response to many extensive studies, a core group of established medical schools and their accrediting agency had developed new guidelines and standards. To say this met with resistance from most established medical schools would be an understatement. Thus, when UCF was given permission to establish a new school, it was expected that we would develop and deliver a curriculum that met the new guidelines, not having to change an established curriculum. New faculty were recruited based on this expectation; existing or established faculty had to learn new tricks.

Fortunately, I had prior experience running a summer microbiology course in a decelerated medical school program for educationally disadvantaged students that relied completely on self-learning – taped lectures, books, computer-aided instructions, and interactive case studies. Students worked both independently and cooperatively. Although these students were considered at-risk, they all did just fine, even without the technological bells and whistles available now. I was prepared to build on that experience.

Extensive medical education reforms have been introduced at all levels, from first year through residency. My own experience was limited to being part of a team teaching a first-year course comprising microbiology and immunology with components of pharmacology and pathology, and occasionally participating in the second year. First I had to learn to change my mindset from “faculty teaching” to “student learning,” and promote student engagement and active (rather than passive) learning. “The Sage on the Stage” was old school; and had no place in the 21st century medical school.

I learned to think about how students learn (they’re all different) and adopt classroom strategies to get and keep their attention – using images and animations, going online for an illustration, using video clips, etc. Class lectures were punctuated with questions to the students based on their recall of facts, or their ability to apply presented material. All classes were videotaped so students could watch in real time from any place, and could review material at any time at their own pace; attendance at lecture was not required. Since students were responsible for material covered in lecture, they had to work out their best mode of learning from all the resources provided.

In addition to promoting engagement in the classroom, the curriculum was designed to be integrated both horizontally and vertically. Horizontal integration was achieved by rolling the separate courses of related disciplines into one. In our case, using cases that illustrate diseases, the organisms causing the disease (microbiology), the damage caused (pathology), the response of the patient (immunology) and the treatment (pharmacology) allowed addressing both basic information and its application to diseases, simulating the experience the student would have facing a patient.

In addition to promoting engagement in the classroom, the curriculum was designed to be integrated both horizontally and vertically. Horizontal integration was achieved by rolling the separate courses of related disciplines into one. In our case, using cases that illustrate diseases, the organisms causing the disease (microbiology), the damage caused (pathology), the response of the patient (immunology) and the treatment (pharmacology) allowed addressing both basic information and its application to diseases, simulating the experience the student would have facing a patient.

In the second year, the organ-based courses were vertically integrated by reprising basic information related to the microbial or immunological cause of diseases of that particular site of the body – usually by the same faculty who taught the relevant material in the first year.

Case studies applying basic science knowledge to clinical situations are widely available and traditionally assigned to students to read, and sometimes to discuss. Students often ignore this passive learning. Instead, we brought the case studies into the classroom, reconfigured to promote active learning. Wet labs and microscopes were replaced with tables and chairs for six to eight students per table, one keyboard and a large monitor at one end of the table. Each group accessed the case studies via computer.

During a “lab” session, each group of students read several paragraphs of a case, and answered on-line questions requiring a search for answers in lecture notes, books and on-line journals before they could advance to the next component of the case. Only one assignment was completed per group – teaching team-work as part of the plan. Answers were collected and reviewed by faculty to ensure students understood the facts and the reasoning. Faculty roamed the room to answer questions, put students back on track if needed, and talk about the case. Some material was covered only in case studies and not in class, providing an incentive for students to actively participate.

We had two years to plan curriculum for the charter class, and we revised some aspects of the course every year as we learned what worked best. Frequent revisions were necessary, especially when our support unit of Educational Technology found new software programs to facilitate the student – teacher interface. Since all textbooks were on line, content and/or illustrations used in the classroom or in test questions had to be updated with new editions.

Once I understood the emphasis on student learning, I was able to focus on promoting and supporting self-directed learning. Our first-year students were on a continuum from those who thought they were still in college to parents with three kids and a different professional life behind them. One of the biggest challenges was to expedite the transition from a college mind-set to a professional mindset. By the time our students graduated, they had to be life-long learners and problem solvers so they could manage the explosion of new knowledge that would be coming at them throughout their professional lives. The school will continue to measure the successful outcomes of our approach; to date our students have done very well on required exams and placed very well in their residencies. Only time will tell whether they practice the habits of mind we encouraged.

My UCF experience did require learning a lot of new technology that was well supported and actually fun to learn. Developing material on new subjects in immunology and working with other faculty to get the clinical aspect right was also challenging and satisfying (i.e. the microbiome, immunotherapy redux). It was a fitting coda to my 50 years in academia and 22 years at UCF – and a segue to retirement! ▼

![]()

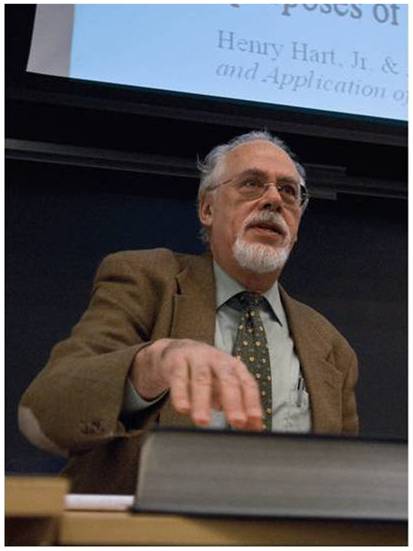

A Lot has Changed: How I Learned, and How I Teach by Peter Strauss

A lot has changed in law school teaching since I began at Columbia Law School 48 years ago, when “The Paper Chase” was the model, and I do feel responsible for some of it.

My subject, Administrative Law, was uniformly taught as if it concerned only the relations between administrative agencies and the courts. Two years on academic leave as General Counsel of an administrative agency taught me how wrong that was. On returning to the classroom (and becoming an editor of one of the leading casebooks on the subject), I helped lead conversion of the course into one that worries deeply about agency internal processes and agency relations with Congress and the President as well as with the courts.

A few transformative summer weeks persuaded me that live discussion in small groups, even in large classrooms, contributed greatly to student learning (Education as Conversation, as our classmate Steven Senturia has been advocating in many ways). Ever since, this use of small groups has characterized my own teaching; and as leader for many years of Columbia’s Seminar on Legal Education, I persuaded many graduate students to the same technique, which they have carried to many law schools in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

A few transformative summer weeks persuaded me that live discussion in small groups, even in large classrooms, contributed greatly to student learning (Education as Conversation, as our classmate Steven Senturia has been advocating in many ways). Ever since, this use of small groups has characterized my own teaching; and as leader for many years of Columbia’s Seminar on Legal Education, I persuaded many graduate students to the same technique, which they have carried to many law schools in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Law school teaching materials have typically relied almost exclusively on judicial case reports as their primary materials, with some ventures into the secondary literature. But law practice today is so often concerned with processes that are not judicial, and with advice that must be given before any court has spoken to the issue. Statutes and regulations, not the common law, dominate as the sources of law today, and most often must be dealt with well in advance of going to court (if, indeed, one must). I’ve developed and promoted materials that make statutes, legislative history, and regulatory materials primary elements of teaching. Actual participation in a live rulemaking has become a significant element of my course.

The coming of the digital age has produced both new resources and new distractions in the classroom, and has transformed student techniques for learning as well. Some colleagues defend against the distractions by banning electronics from their classrooms. I’ve long resisted that, and built elements into my teaching that require students to explore and use the rich new resources that the electronic age makes available, and that they will need to use in their profession. Books like “The Shallows” and “The Dumbest Generation” decry the digital age’s impact on learning. Looking the other way is Catherine Davidson’s “The New Education,” and it has inspired approaches that I believe contribute significantly to student engagement and learning.

For each class I assign computerized notetaking to three students, who are to produce a single set of notes posted for the class and sent to me, ending with any matters that in their judgment warrant further clarification or comment. After perhaps half a minute of breathing together, for focus, the next class opens with those questions. Then, Davidson-inspired, each student has 90 seconds to write, on index cards I distribute, responses to assignment-related questions I put; the next 90 seconds are for reciprocal sharing with a colleague next to them; and then I call on a number of the pairs to share their findings with all of us, helping to frame the day’s class. Learning is a collective responsibility, these measures say again and again. ▼

![]()