Class Newsletter #4, Holiday Issue

We hope this Holiday Issue, and last issue of 2018, will bring Good Cheer. We thank all eight 1961 Class Member Contributors on this

Theme of Community, and Wish Everyone a Happy New Year.

|

|||||

had reached out to help shelters for the homeless in their communities. Formerly homeless individuals were also there, speaking about how their lives have improved. The court case will be decided soon. My own neighbors are still skeptical, but at least they have said they will help make the shelter a model if the case is decided in favor of the City. ▼

![]()

Selecting a Community by Ruth Scott

The lawsuit alleging that Harvard discriminates against Asian Americans went to trial in Boston on October 15, 2018. A July 29 New York Times article about the case described the Harvard admissions system as “arcane…filled with whims and preferences,” noting that some candidates were described as “very busy” while others were called “compelling.” I was a Harvard alumni interviewer for years and an admissions officer at Princeton in the first year of coeducation. I truly believe in their similarly “arcane” admission systems.

After the initial readings and ratings, the officers assess the remaining pool. Will the person adapt well and grow? Has he achieved on his own? Clues can be found in close reading of teacher or counselor recommendations, interviewers’ reactions, and the applicant’s essays. Per “School Colors” by Hua Hsu in the October 15, 2018 New Yorker, asserts that the “personal” category is the problem. I maintain that it is the key.

After the initial readings and ratings, the officers assess the remaining pool. Will the person adapt well and grow? Has he achieved on his own? Clues can be found in close reading of teacher or counselor recommendations, interviewers’ reactions, and the applicant’s essays. Per “School Colors” by Hua Hsu in the October 15, 2018 New Yorker, asserts that the “personal” category is the problem. I maintain that it is the key.

Letters of recommendation: When there is genuine enthusiasm, it shows. At Princeton I received a glowing recommendation for a young man who had good grades and scores but not much else. I phoned the teacher who convinced me that he was truly exceptional. He was. He graduated first in his class at both Princeton and Harvard Law School.

Interviewers’ write ups: Sometimes parents wanted to be present for the interview. Not a good idea. Sometimes students tried too hard to sound brilliant or spent time explaining their class rank instead of talking about learning.

There were other candidates whom you WANTED to join the Harvard community. One cheerful young man drove to my house in a wreck of a car which would not start after the interview. He returned apologetically and asked if he could use the phone to call his father. I watched them work together to jump start the car and wrote it up.

A Chinese student from a local boarding school explained to me that his parents were in China, so during school vacations he worked at a Chinese restaurant, living in a dorm with older Chinese waiters. This information was more “compelling” than just “very busy.”

Essays: Some essays are dull, many appear to have been edited by third parties. By contrast, other essays are memorable. One young man whose parents were Russian immigrants wrote that they had a “serf mentality”, and he did not, giving examples. Another wrote about how he loved to juggle, because he liked to be the center of attention. He sounded like a good guy, and his teachers thought so, too.

Good admissions officers really care about the college and the applicant. When the sports teams were selected and first freshman marks were posted at Princeton, we all rushed to see how “our” admits had done. We hoped that they were thriving.

As President Bacow said in his recent email: “I want you all to know that each Harvard College student is admitted affirmatively. Each student brings something special to our community.” ▼

![]()

Charles Sander Peirce: Truth as a Community Achievement by Gilbert W. Merkx

Harvard graduate Charles Sander Peirce (1839-1914) was simultaneously a mathematician, scientist, and philosopher, best known as the founder of philosophical pragmatism. Peirce was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father was Harvard Professor Benjamin Peirce, the first American research mathematician. Peirce was studying logic by the age of 12. As an undergraduate he immersed himself in Kant. He received his AM and MA in 1862, and in 1863, Harvard’s first BSc degree in chemistry. Peirce became a research scientist for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, while also doing research in the Harvard Observatory and teaching philosophy at Johns Hopkins from 1879-1884.

Despite his career as a working scientist, Peirce wrote hundreds of papers on mathematics, logic, and philosophy. After leaving the Survey in 1891 he became even more productive. Today Peirce is recognized as a foundational thinker in important fields such as the theory of signs (semiotics), symbolic logic, statistical inference, logical syntax, and lattice theory (a forerunner of network analysis).

Peirce’s pragmatic philosophy offered an alternative to Cartesian dualism and a reconfiguration of Kant’s philosophy. Peirce challenged Descartes’ two key assumptions: first, Descartes’ radical doubt of the existence of the material world, and second, his confidence in the existence of the individual mind (“I think, therefore I am.”). In contrast, Peirce subscribed to a “common sense realism,” or confidence in an independent world of external things that exist very much as we experience them. As Peirce observed in his Selected Writings, “We cannot begin with complete doubt… Let us not pretend to doubt in philosophy what we do not doubt in our hearts.”

With respect to the question of the “I” or individual mind, Peirce argued that knowledge and thinking are not purely intuitive processes but are also social in character. We think in language, and language is composed of signs or symbols whose meaning is socially determined. Moreover, every cognition is logically dependent on previous cognitions which result from the sharing of experiences.

With respect to the question of the “I” or individual mind, Peirce argued that knowledge and thinking are not purely intuitive processes but are also social in character. We think in language, and language is composed of signs or symbols whose meaning is socially determined. Moreover, every cognition is logically dependent on previous cognitions which result from the sharing of experiences.

Peirce’s rejection of the Cartesian assumptions was not a complete rejection of dualism, but rather a reformulation in which the reality of the world is taken for granted but must be verified by research. Truth and mind are seen as products of social interactions, and not solely of intuition or reflection.

Peirce had far more respect for Kant’s philosophy than for Descartes’. However, Pierce considered certain aspects of Kant’s logic to be faulty. Kant had described his philosophy by saying: “I call all knowledge transcendental if it is occupied, not with objects, but with the way we can possibly know objects even before we experience them, or a priori.” Kant thus distinguished between a priori or transcendental knowledge and a posteriori or empirical knowledge. He argued that transcendental knowledge is made possible by the pre-existing prime categories of the mind, such as number, color, and time, which are also categories of the real world.

Peirce revised Kant’s transcendental philosophy by arguing that the categories of mind are not innate to the mind but rather exist in ordinary language or special languages used by the observer. Peirce’s position on categories is part of his theory that signs, or semiotics, are essential for meaningful communication. The three basic elements of Peirce’s semiotics were the sign, the object signified by the sign, and the sign’s meaning or implication (as held in the mind of the perceiver), which he called the interpretant (interpretation). Interpretants are themselves signs that can lead to further interpretations, in a continuing cycle.

Peirce viewed inquiry as a process whereby signs are transformed into other signs while maintaining a specific relation to an object, and he considered “the right method of transforming signs” to be the scientific method. Peirce’s view of the scientific method parted company with Kant’s view, because Peirce considered science to be a community effort, not the relationship between the transcendental and the empirical in the mind of one single observer. In Peirce’s words, “To make single individuals absolute judges of truth is most pernicious. In sciences in which men come to agreement, a theory is considered to be on probation until agreement is reached. We individually cannot reasonably hope to attain the ultimate philosophy which we pursue; we can only seek it, therefore, in the community of philosophers.”

Peirce’s theory of truth provides the clearest illustration of his differences with Kant. As Peirce observes, “That truth is the correspondence of a representation with its object, as Kant says, is merely the nominal definition of it.”

Peirce viewed this “nominal” definition as dyadic, consisting of only two elements (representation and object), as contrasted to a “real” definition (as in real world), which would have to be triadic, consisting of the object, sign, and interpretation. Both the sign and the interpretation are social in character. Triadic, or real truth, is thus, by its very nature a social process involving the community of researchers. Peirce’s view of truth is also made clear in the following quote from Vol 5 of his Some Consequences of Four Incapacities:

“The real then, is that which, sooner or later, information and reasoning would

finally result in, and which is therefore independent of the vagaries of me and

you. Thus, the very origin of the conception of reality shows that this conception

essentially involves the notion of a community.”

Peirce’s theory of truth replaced the correspondence theory of the dualist philosophers with a consensus theory requiring a common language and a collective research effort. Thus, nominal truth (truth by correspondence) can result from an individual investigation but may be fallible (erroneous), while real truth (truth by a consensus emerging in the research community) is an outcome of a collective effort of verification. In effect, Peirce replaced Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am" with “We agree, therefore it is.” ▼

![]()

Arctic Passion by Anne S. Douglas

I first went to Arctic Bay in 1991 as a McGill University doctoral student in educational anthropology. This was the most recently settled community on Baffin Island, in what is now Nunavut. Inuit were still moving in from their family camps in the late 1970s. Inuktitut was the common language and the only language for most. Inuit in this region began to adopt Christianity in the 1920s. Many reaffirm their traditional values through Christian practices.

A late phone call interrupted my packing. It was Rebekah in Arctic Bay, requesting a couple of items from Montreal. I told her I was leaving early in the morning, and could only shop at the airport. Her needs were a particular type of baby bottle and a crown of thorns. I said I’d try to find the bottle, but the crown of thorns wasn’t possible. I explained my commission to the friend who drove me to the airport. Most Inuit would find conceptualizing a crown of thorns challenging; Inuit need to see something to fully comprehend its significance. “I wish I could help you!” my friend said as we unloaded my bags. I couldn’t find the bottle and thus, six hours later, arrived empty handed in the High Arctic. It was extremely cold, but the light was returning rapidly. In two weeks, by the time of the vernal equinox, daylight would last for twelve hours. Although Easter was over a month away, the community was already planning a Passion Play, hence the need for the crown of thorns. The play would be a new experience here.

The week before Easter, a choir began rehearsing the mournful evangelical hymns introduced by the missionaries. We sang in both Inuktitut and English. I didn’t know many of the Inuktitut words, but I could read and pronounce the syllabics. On Tuesday morning the post-mistress told me I had a package. It was flat and square, and looked like a pizza box. And that’s exactly what it was! My Montreal friend had found some hawthorn bushes—in the box lay a crown of cruel thorns.

The week before Easter, a choir began rehearsing the mournful evangelical hymns introduced by the missionaries. We sang in both Inuktitut and English. I didn’t know many of the Inuktitut words, but I could read and pronounce the syllabics. On Tuesday morning the post-mistress told me I had a package. It was flat and square, and looked like a pizza box. And that’s exactly what it was! My Montreal friend had found some hawthorn bushes—in the box lay a crown of cruel thorns.

Not a chair was empty in the Anglican Church on Good Friday. The half-dozen Catholics and the twenty or so practicing Pentecostals came too, the usual custom on community-wide occasions. A large wooden cross about eight feet long lay against the chancel steps, with a tin of nails and a hammer beside it. After his homily, the priest, Jonas Allooloo, asked us to come and hammer a nail in the cross if we believed Jesus had died for our sins. Some people leant forward and covered their faces with their hands. Others began to sob silently, overcome with a recognition of self-betrayal. Then, one by one, people went forward to the chancel, picked up a nail and hammered it in. I was drawn into the ritual, and hammered in my own nail. The community was quiet for the rest of the day. The Passion Play was scheduled for the following night.

On Saturday evening at 7 we gathered in the school gym-cum-community hall. The choir, sitting near the front, sang while people arrived. As Jonas read the gospel account of Jesus’ trial in Inuktitut, the characters of the passion began to enter. First came Pilate, who climbed up onto the gym stage and sat down on a chair in stage-centre. No one undertook the role of Jesus, but Kigitikarjuk Shappa was cast as Mary, his mother. This evening, her usually tightly-braided hair flowed down over the shoulders of her blue gown. I was moved by the grace and dignity with which she undertook her role, particularly so as her husband was serving a sentence in the Baffin Correctional Centre. She entered from the side, then, climbing onto the stage, stood some distance to the right of Pilate.

Then came Joseph Okadluk as Judas, holding his bag of silver. He climbed the stage and deposited the small sack on a table to Pilate’s left. Next, Naqitarvik marched down the centre aisle, wearing caribou clothing and carrying a powerful dog whip to represent the scourgers. He placed the whip beside the bag of silver. A lone Inuk followed, bearing the crown of thorns in its open box. This joined the other two items on the table. Once Jonas had finished reading, everyone in the hall filed onto the stage to view the two instruments of torture and the bag containing the coins of betrayal.

The Passion Play wasn’t intended as entertainment. It was a representation of our human community. The tragedy was our tragedy; we were the betrayers. As with classical Greek tragedies, the drama provided opportunities for people to experience those human passions which harm the social fabric when they occur in every-day life. The authentic pain of shared shame and sorrow paves the way for the absolution of compassion and forgiveness, and the community is restored to wholeness.

We sang more optimistic hymns on Sunday, but the resurrection really began on Monday with games on the frozen bay. Everyone wore their best parkas, kamiks, and mittens. After participating in some familiar races, I lined up for the women’s harpoon throw. I watched apprehensively as the women ahead poised the long metal weapon over one shoulder, then thrust it forward towards the target. To my relief—although to my competitors’ disappointment—my harpoon sailed through the air and landed in the snow at the target’s base. The games continued until 6pm. Then we gathered in the gym from 7 until midnight for more games and dancing. The celebration lasted for the next two days, culminating in an igloo building competition on Wednesday.

The Inuit have always put community first because group cooperation was once essential for their survival. The ideal continues to hold moral value for them. They have taught me that people who prioritize community accept their transparency to one another. Human limitations and frailties—one’s own and those of others—are easier to accept within the frame of this understanding. ▼

![]()

War Poets by Richard Barthelmes, with Editor's supporting research

|

|

In the fall of 1920, Harvard commissioned John Singer Sargent to produce two paintings for the main stairwell at Widener Library as part of the University’s tribute to its World War I dead. Surprisingly, despite over 9 million military deaths (more than half on the Allied side), the mural on the left glorified – and still does -- the grim price exacted by war. A lone soldier (a Harvard grad?) is gripped closely by the partly shrouded figure of Death and embraces the form of beautiful, luminous Victory, her palm branch held high. Beneath his feet lies a fallen German, amid blood, barbed wire, and ammunition — the mortal enemy defined. A virtual altarpiece for a youthful martyr, the painting seems imbued with jingoistic fervor. The “Great War” was not viewed in the same light by many of those who experienced it at first hand. A community of young men who were at the same time soldiers and poets came to prominence in Britain during and after the war. At the outset, a few – most notably Rupert Brooke and Julian Grenfell -- welcomed war as giving one’s life a constructive purpose, and saw death in combat as an honorable, almost desirable road to immortality. But, as the grotesque brutalities of trench warfare became apparent, the tone, themes, and even the form of wartime poetry underwent radical changes. |

|

A few examples illustrate the discontinuity been the reality of combat soldiering and the outdated imagery of Sargent’s murals. Siegfried Sassoon, the Cambridge-educated scion of a prosperous Jewish family, served as an officer with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. His personal bravery was legend among his troops, who called him “Mad Jack,” and in 1915 he was awarded the Military Cross. What he experienced, however, requied expression in poetry. “Counter-Attack” describes British soldiers digging in to resist an expected German assault:

Things seemed all right at first. We held their line,

With bombers posted, Lewis guns well placed,

And clink of shovels deepening the shallow trench.

The place was rotten with dead; green clumsy legs

High-booted, sprawled and grovelled along the saps

And trunks, face downward, in the sucking mud,

Wallowed like trodden sand-bags loosely filled;

And naked sodden buttocks, mats of hair,

Bulged, clotted heads slept in the plastering slime.

And then the rain began,—the jolly old rain!

The poem recounts the experience of a single soldier during the preliminary artillery bombardment. “He crouched and flinched, dizzy with galloping fear, sick for escape,—loathing the strangled horror and butchered, frantic gestures of the dead.” And when the attack finally comes: ““O Christ, they’re coming at us!” Bullets spat, and he remembered his rifle ... rapid fire ... and started blazing wildly ... then a bang crumpled and spun him sideways, knocked him out to grunt and wriggle: none heeded him; he choked and fought the flapping veils of smothering gloom, lost in a blurred confusion of yells and groans ... down, and down, and down, he sank and drowned, bleeding to death.”

Sassoon also published several overtly “political” poems attacking the conduct of the war, including “The General”:

Good-morning, good-morning!” the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of 'em dead,

And we're cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

“He's a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

While on leave in England, Sassoon lodged a written protest with the War Department, which stated in part: “I believe that this War is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it.” He further infuriated the establishment by publicly tossing his Military Cross into the River Mersey. There was talk of court-martial, but fellow poet Robert Graves persuaded the authorities to allege that Sassoon suffered from shell-shock and that his addled mental state explained his actions. He was sent to a psychiatric hospital in Craiglockhart, Scotland, but later returned to combat.

Wilfred Owen, from a middle-class Welsh family, joined the Artists’ Rifles in 1915. Much loved by his troops, he served as an infantry officer until he was killed a mere week before war’s end, leading a charge against a German position. Encouraged by Sassoon, whom he had met at Craiglockhart, Owen wrote some of the most moving poems to emerge from the war. Nine of his poems form the text of Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem” oratorio (1962).

“Dulce Et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori” describes a gas attack on Owen’s unit, and the death of one of his men who failed to get his gas mask in place quickly enough:

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

“Strange Meeting”, “Mental Cases” and “Disabled” (accessible at www.poetryfoundation.org) are among other striking examples of Owen’s linguistic gift and profound humanity.

Isaac Rosenberg was one of the few war poets who served as a private soldier. His parents were Russian immigrants and as a child he worked in his father’s butcher shop. Forced by economic circumstance to leave school at age 14, he worked as an engraver’s apprentice. He showed so much talent for the visual arts that he won a scholarship to the famous Slade Art School, but began writing poetry before the outbreak of war. From “Break of Day in the Trenches”:

The darkness crumbles away.

It is the same old druid Time as ever,

Only a live thing leaps my hand,

A queer sardonic rat,

As I pull the parapet’s poppy

To stick behind my ear.

Droll rat, they would shoot you if they knew

Your cosmopolitan sympathies.

Now you have touched this English hand

You will do the same to a German

Soon, no doubt, if it be your pleasure

To cross the sleeping green between.

It seems you inwardly grin as you pass

Strong eyes, fine limbs, haughty athletes,

Less chanced than you for life,

Bonds to the whims of murder,

Sprawled in the bowels of the earth,

The torn fields of France.

What do you see in our eyes

At the shrieking iron and flame

Hurled through still heavens?

What quaver—what heart aghast?

Poppies whose roots are in man’s veins

Drop, and are ever dropping;

But mine in my ear is safe—

Just a little white with the dust.

And from “The Dead Man’s Dump”, which describes driving a cartload of rusted barbed wire and iron stakes to the front line:

The wheels lurched over sprawled dead

But pained them not, though their bones crunched,

Their shut mouths made no moan.

They lie there huddled, friend and foeman,

Man born of man, and born of woman,

And shells go crying over them

From night till night and now.

Earth has waited for them,

All the time of their growth

Fretting for their decay:

Now she has them at last!

In the strength of their strength

Suspended—stopped and held.

What fierce imaginings their dark souls lit?

Earth! have they gone into you!

Somewhere they must have gone,

And flung on your hard back

Is their soul’s sack

Emptied of God-ancestralled essences.

Who hurled them out? Who hurled?

War memorials such as the Widener murals have always been intended to honor the dead. Less excusably, they have also sought to inspire younger generations to enlist in future wars. Are not the poems of those who truly knew war a far better memorial? . ▼

![]()

The Natural Origins of Altruistic, and Community-Building Behavior: A True Instinct, by Don Pfaff

A couple of years ago I was beginning to cross Third Avenue in Manhattan on a hot summer afternoon. A limousine had stalled in a middle lane and a fat, sweaty stroke-ready driver was about to push it. Crossing the street was a beautifully dressed guy with a briefcase. That guy put down his briefcase and helped the driver push the limo out of the way. Why did that guy do that?

A couple of years ago I was beginning to cross Third Avenue in Manhattan on a hot summer afternoon. A limousine had stalled in a middle lane and a fat, sweaty stroke-ready driver was about to push it. Crossing the street was a beautifully dressed guy with a briefcase. That guy put down his briefcase and helped the driver push the limo out of the way. Why did that guy do that?

My book The Altruistic Brain (Oxford University Press) lays out brain mechanisms and shows that altruistic behaviors are natural consequences of ordinary mechanisms in the human brain. No supernatural influences necessary. Details of motor pathways and sensory mechanisms are arranged such that internal, neural representations of the person toward whom we are about to act and our own images can be merged. Then, a value-laden decision process completes the deal.

In the history of vertebrate species, the most primitive prosocial behaviors are reproductive behaviors. My lab at the Rockefeller University worked out the hormonal, neural and genomic mechanisms for one of these (How the Vertebrate Brain Regulates Behavior; Harvard University Press). Now we are onto more medically related topics - the brain mechanisms necessary to emerge from deep anesthesia, deep sleep or traumatic brain injury (How Brain Arousal Systems Work: Paths Toward Consciousness; Cambridge University Press).

But there are reasons to worry. I just read that Oxford biology professor Robin Ian Dunbar is wondering whether social brain mechanisms sufficient to manage social behaviors in small groups might be about to fail in some of our dense, huge nations. Does that remind you of anything? ▼

![]()

Inventing the N-Localizer for Stereotactic Neurosurgery: the Story of a Young Researcher in Radiology and Imaging Sciences, by Jim Nelson

[Much of the following text comes from an article by Michael Mazdy in a University of Utah School of Medicine Newsletter ]

In 1978, I was a radiologist doing research at the University of Utah School of Medicine (the “U”). One day a tall, red-headed 3rd-year medical student came to my office. Russ Brown was casting about for a research topic. I suggested neurosurgery, specifically stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), a field which at the time was plagued by imprecision. Despite its name, SRS is a non-surgical radiation therapy used to treat functional abnormalities and small tumors of the brain. When precisely targeted, it can deliver radiation in fewer, higher-dose treatments than traditional therapy, thus preserving healthy tissue.

In 1978, I was a radiologist doing research at the University of Utah School of Medicine (the “U”). One day a tall, red-headed 3rd-year medical student came to my office. Russ Brown was casting about for a research topic. I suggested neurosurgery, specifically stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), a field which at the time was plagued by imprecision. Despite its name, SRS is a non-surgical radiation therapy used to treat functional abnormalities and small tumors of the brain. When precisely targeted, it can deliver radiation in fewer, higher-dose treatments than traditional therapy, thus preserving healthy tissue.

I agreed to coach Brown, and his efforts led to a true team effort that became a small ‘research community’ with a common purpose.

In his third year at the “U’”, Brown had realized that he preferred math and computers to direct patient care. “I needed to find a research elective,” he later recalled, “or my fourth year of medical school would be filled with numerous clinical rotations that didn’t appeal to me.” Because of his background in computer science, Brown was interested in imaging research. I convinced him that, building on the precise geometry of CT scans of the brain; he might find it interesting to work on improving stereotactic neurosurgery. He did extensive reading and after several follow-up meetings, disappeared for about a month. When he returned he said, 'I've worked out the solution. I know how to make it work.’” In fact, during that month, Brown had come up with something that would change neurosurgery forever: a device known as “the N-Localizer”.

“You’re the guy who saved my wife’s life,” is a phrase few researchers expect to hear during their lifetimes. Since his days at the U when he invented the device, Brown (now M.D., Ph.D.) personally met a number of people whose loved ones have undergone neurosurgery guided by the N-localizer. He marvels at how what began as an elegant mathematical solution has led to life-saving neurosurgical interventions for more than a million patients.

Stereotaxis and the Educated Guess

Performing any kind of procedure on the brain is not easy. There’s the problem of the hard skull and a squishy brain underneath, which make getting inside tricky and dangerous. More importantly, physicians need to know the exact point at which to operate, as a few millimeters’ misstep in any direction could be disastrous.

Formerly, any stereotactic procedure was very dangerous; if the surgeon missed the intended target by even a few millimeters, the patient could end up in a vegetative state. By the late 1960s, the drug L-DOPA was introduced as a medical treatment for Parkinson’s disease and stereotactic surgery fell into disuse. But with the invention of the computerized tomography (CT) scanner, stereotactic surgery was poised for a thrilling comeback by the mid-1970s. Suddenly, neurologists had access to images of the brain with exquisite contrast. If there were a way to correlate the CT scan to the three dimensions of physical space around the patient’s head, then neurosurgeons could perform stereotactic surgery with much greater accuracy and safety.

Nothing a Little Triangulation and Linear Algebra Can’t Solve

Physician researchers were trying to tackle the problem of merging CT scans and stereotactic surgery when Brown first met with me about a research elective. After reading the published studies I gave him, Brown began to get some ideas. “There was no mathematical sophistication,” Brown relates, “The problem wasn’t even articulated very well. There was no way to enforce a relationship between the scan image and the stereotactic frame.”

CT scans are a collection of two-dimensional x-ray images, each taken as a “slice.” CT slices may contain a point of interest for a physician, but translating that two-dimensional point to the three dimensions of a patient’s head in a stereotactic frame is not a trivial task. “It was necessary to transform (u, v) coordinates from the two-dimensional coordinate system of the CT image into (x, y, z) coordinates in the three-dimensional coordinate system of a stereotaxic frame,” Brown explains. But there was no consistent point of reference in the CT image or on the frame that could help to orient and connect the two.

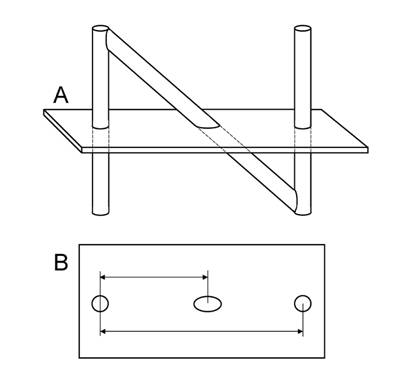

Brown’s clear understanding of the problem, coupled with his knowledge of geometry and linear algebra, led him to an elegant solution that could be manufactured directly into a stereotactic frame. He realized that attaching a diagonal rod to the frame would produce an elliptical landmark in the CT image. As the CT scans moved progressively upward with respect to the diagonal rod, the ellipse that marked where the rod intersected the slice would move from one side of the CT image to the other. Better yet, he realized that placing the diagonal rod between two vertical rods to form an “N” would produce two circles that mark fixed beginning and end points for measuring the movement of the ellipse (see illustration).

The concept behind the N-localizer: A) shows the N-shaped combination of rods and the intersection of these rods with the CT scan plane, and B) shows the resulting CT image. The circles and ellipse are produced by the intersections of the rods with the CT scan plane. As this plane moves upward with respect to the diagonal rod, the ellipse moves away from one circle and towards the other circle. Measurement of the distances between the circles and the ellipse provides information to orient the CT image to the stereotactic frame.

The concept behind the N-localizer: A) shows the N-shaped combination of rods and the intersection of these rods with the CT scan plane, and B) shows the resulting CT image. The circles and ellipse are produced by the intersections of the rods with the CT scan plane. As this plane moves upward with respect to the diagonal rod, the ellipse moves away from one circle and towards the other circle. Measurement of the distances between the circles and the ellipse provides information to orient the CT image to the stereotactic frame.

The next challenge for Brown was that CT scanners have some mechanical imprecision, meaning that the plane of the CT scan slice could be oriented in any position relative to the frame. Brown needed to know exactly how the slice was oriented with respect to the frame, so he placed three N-localizers on the frame so they would encircle a patient’s head. This way, any CT slice contains three different points that intersect the N-localizers and thereby define the plane of the CT scan.

Three N-localizers precisely determine the orientation of the CT scan plane (the rectangle) relative to the base of the stereotactic frame (the oval). Brown used the intersection points Pʹ1, Pʹ2, and Pʹ3 of the diagonal rods to transform the target point PT from the two-dimensional coordinate system of the CT image into PʹT in the three-dimensional coordinate system of the stereotactic frame.

Three N-localizers precisely determine the orientation of the CT scan plane (the rectangle) relative to the base of the stereotactic frame (the oval). Brown used the intersection points Pʹ1, Pʹ2, and Pʹ3 of the diagonal rods to transform the target point PT from the two-dimensional coordinate system of the CT image into PʹT in the three-dimensional coordinate system of the stereotactic frame.

Because three N-localizers provided Brown with the points of intersection and the plane of the CT scan, he was able to utilize what is called a matrix transformation; a little bit of linear algebra that helps to convert two-dimensional points into a three-dimensional coordinate system and vice versa. That gave him what the neurosurgeons need: an exact (x, y, z) coordinate within the patient’s brain that they could access.

“The N-localizer made neuro-navigation possible”

From Concept to Widespread Neurosurgery

Brown then made a model frame out of plastic, and we tested the performance by localizing lead shot laced into a cantaloupe. It worked perfectly! Using a clinical device, neurosurgeons could simply type into a handheld calculator the (u, v) coordinates of the point of interest identified by a CT Scan. Brown’s software (which he wrote using principles he had learned while working at Evans and Sutherland, the world’s first computer graphics company) would return the four arc angles and a depth that the neurosurgeons would use to reach their target.

Brown began testing the device. Using CT scans of the frame and spheres, Brown dialed the appropriate angles into the stereotactic frame and successfully targeted the spheres. The device was as accurate as Brown had hoped, achieving an average deviation from the target point of only 2 mm.

I encouraged Brown to demonstrate the prototype for Ted Roberts, MD, the chief of Neurosurgery at the U. Roberts immediately saw its value and asked his colleague Peter Heilbrun, MD, to help test this tool in the operating room. The two were both pilots, and their experience in navigating the skies gave them insight into how important Brown’s invention was for navigating the brain. But they needed to find someone who could manufacture a stereotactic frame with built-in N-localizers. They knew just the man for the job: Trent Wells, an former pilot who had flown P-51 Mustang fighters in World War II. Wells had spent the past 30 years building medical instruments, including other stereotactic frames for use with CT scanners, but that lacked the N-localizers.

Wells was intrigued, and after some discussion with Brown and Roberts, retreated to his workshop to engineer the manufactured model. Wells turned the idea into the Brown-Roberts-Wells stereotactic system, or BRW frame. This production frame was even more precise than the prototype, achieving an average deviation from the target point of a mere 1 mm.

Once neuro-navigation became possible, it turned out to have many applications. It has been used with CT, magnetic resonance (MR), and positron emission tomography (PET). Neurosurgeons have used it to guide tissue biopsies, evacuations, aspirations, and cultures; to guide functional neurosurgery, in which various brain structures are intentionally destroyed; and to guide brachytherapy, which places sealed radiation sources inside or adjacent to a brain tumor in order to kill the cancerous cells. And probably the most important application of the N-localizer is to guiding SRS, which utilizes external x-rays or gamma rays to destroy the cells of a brain tumor. more than a million patients have been treated with this technique, utilizing the device thar originated as Russ Brown's invention. ▼

![]()

Scholarship Plus, Part I of II by Soma Behr

The Communities where we spend their lives are usually communities of our own kind. That was surely so at Radcliffe, and later at The New York Times, where I spent 30-plus years as reporter and editor. We struggled for diversity but never really got there.

I found diversity initially through my journalism. I had been one of very few women majoring in economics at our alma mater and was stirred by liberal Harvard professors who believed that good government policies could lead to a more equitable society. As a reporter and editor, I spearheaded major projects. I used a journalist’s tools and The Times’ deep bench of great reporters and editors to follow the story.

I was especially proud of three very large, prize-winning projects that I led: one about 10 young kids forced to live hard lives in the shadowy streets of our cities; another about how race affects the worlds of Americans living seemingly parallel lives, and third, the elusive story of class in this country.

The last project showed that poor and working class Americans had begun losing traction in the race up the economic ladder years before Donald Trump came on the scene and won their votes. The statistics generated for that series, “Class Matters,” were scary. They showed that for many of our fellow citizens, the American dream had become a nightmare of frustration.

That depressing series also marked the end of my journalism career. I was close to my 66th birthday, a time when almost all top editors of the New York Times must evaporate from the newsroom to make way for the next generation.

I agreed with the policy in theory but the pending reality threw me into a mild panic. I was not ready to write my autobiography as so many friends had. Nor did I have a hobby to pour myself into.

Then the gold ring came my way – and I grabbed it. I was invited to run the innovative New York Times College Scholarship Program, which had been created in the newsroom in 1999 and enthusiastically embraced by many reporters and editors, including myself.

Life changed dramatically but I stayed focused on my old passion for socio-economic progress, merely switching my focus from macro-economics to micro, from generalizations about millions of poor Americans to specifics about hundreds of them. I left my perch high on The Times masthead and began to work on the ground to help students from the rough streets of NYC succeed on the manicured campuses of the upper-middle class.

The Times program offered 4-year scholarships to 20 NYC high school graduates. The applicants had to be poor, bright and determined. They had to show, during their high school years, a passion for learning as well as the grit and determination needed to make it in college.

The Times started out rather innocently, thinking of itself primarily as a check writing program, with summer internships for the new class. They realized quickly that helping needy students make it through college would mean helping them with all kinds of problems, academic, financial and personal.

For me it was a steep learning curve. But I loved every minute of it. It was exciting to join a new community where people came from different worlds. Oddly, I felt the same sense of excitement that I’d experienced when I discovered my passion for journalism in a 9th grade writing class 50 years earlier.

Each winter we winnowed down over 1000 applications to select the 20 winners. It was a painful process for everyone. We left behind hundreds of fantastic kids who could’ve benefited greatly from the program. We would have loved to do more.

But suddenly, in the middle of 2008, the economy plunged into a recession. With new digital technologies battering the profits of old media, even the mighty New York Times seemed threatened.

Worried executives made substantial cuts to the scholarship program substantially and threatened even more. I thought such drastic cuts were unnecessary and fought the move. Costs could be trimmed and I thought we could draw funds from a multi-million dollar endowment given to The Times a few years earlier specifically for the scholarship program. So why the panic? The answer was lost in the chaos and so was my battle. Hence, I retired from The Times for the second time --this time for real.

By then, however, I was hooked on my new career. I believed that a college education could pay off for everyone, including the poorest kids from the worst high schools, if they were determined to succeed. Trusting to my instincts and experience, I set out to jumpstart a new program for the next spring with at least five new high school graduates on board.

I admit that I had more of a passionate commitment than a financial blueprint when we launched. But I had two major donors who agreed to come with me, and one retired colleague from The Times business side, who became cofounder. I had a pretty good Rolodex myself, many useful contacts from my decades at The Times, and a passion for the task.

I quickly found an outstanding media company to join hands with us: New York Public Radio. Its president, Laura Walker, offered us paid summer internships, mentors and space for group events. Next, I met Mary McCormick, head of the well-respected Fund for the City of New York, who offered to put our baby program in her “incubator” for nonprofits. This immediately gave us the 501(c)(3) status needed to solicit tax deductible donations. All we had to do was find the donors.

We named the program Scholarship Plus, to underline our twin commitment to offer financial help PLUS an array of personal support for students. And went to work. Our goal to have our first class the next June meant we had to hurry to write and distribute hundreds of application forms to high school advisers and to organize a selection committee to pick our winners. Some students interviewed that first year weren’t sure we were legitimate. But my credentials and our quickly-designed website (www.scholarshipplus.org) convinced them.

We named the program Scholarship Plus, to underline our twin commitment to offer financial help PLUS an array of personal support for students. And went to work. Our goal to have our first class the next June meant we had to hurry to write and distribute hundreds of application forms to high school advisers and to organize a selection committee to pick our winners. Some students interviewed that first year weren’t sure we were legitimate. But my credentials and our quickly-designed website (www.scholarshipplus.org) convinced them.

We met amazing kids. Some had spent years of their childhood moving in and out of homeless shelters. Most were from fractured families. Some survived by living alone in cheap rooms and working as baristas. Others spent their nights crowded like sardines on the floors of unsafe apartments filled with illegal immigrants. They studied wherever they could find room to think on subways and buses, in bathrooms and under dinner tables. Most were the first in their families to go to college. In many cases their single parent was more eager for them to make money than straight A’s.

Ours could not be a one-size-fits-all program. Though we try to keep our students debt free, some borrow money despite our advice and a few colleges simply refuse to let us eliminate a student’s loans with our grant. We provide other kinds of financial advice, lectures to prepare students for many aspects of college life, and a variety of cultural experiences in New York. We enlist help on and off campus from academicians, mentors, therapists and professionals in fields of student interest, and monitor those relationships. Throughout college, we help scholars find summer jobs or paid internships to prepare for the post-college workplace. And we have created a vibrant support community for student during and after college. Our students need never feel alone.

Less than a year after our birth, in June 2010, we had a small but spirited welcome party in the cafeteria at New York Public Radio for our first class of six students, their families and friends. Each proud but anxious student also honored a teacher who had made the biggest difference in his or her life. Emotions ran high. ▼ (to be continued in a subsequent Newsletter issue)

![]()